THE EXHIBITION

In 1944-1945, the liberation of Europe unleashed a wave of relief, joy and hope. At the same time, it also led to new domestic and international political tensions. The emergence from genocide was also long and chaotic. A minority of the tens of millions of displaced persons and refugees were rare Jewish camp survivors, whose fates varied widely from one end of Europe to the other. In some countries, such as Hungary and Romania, a new resentment fuelled long-entrenched hatred and survivors had no choice but to flee. But where could they go? The distress and misery of Jews at the end of the war can hardly be imagined. Many were homeless and jobless, and no longer had families or resources. The refugees were stateless. They needed outside help to return to “normal life” . Governments and Jewish organisations, especially American ones, offered financial, material and social assistance to meet the needs of European Jews who had survived the genocide. But obtaining justice and building a memory of the Holocaust were also immediate needs. As early as 1945-1946, funeral rites and commemorations took place and monuments and memorials were built. Survivors faced various situations after the war. In the exhibition they are exemplified by five individual itineraries.

EMERGING FROM GENOCIDE

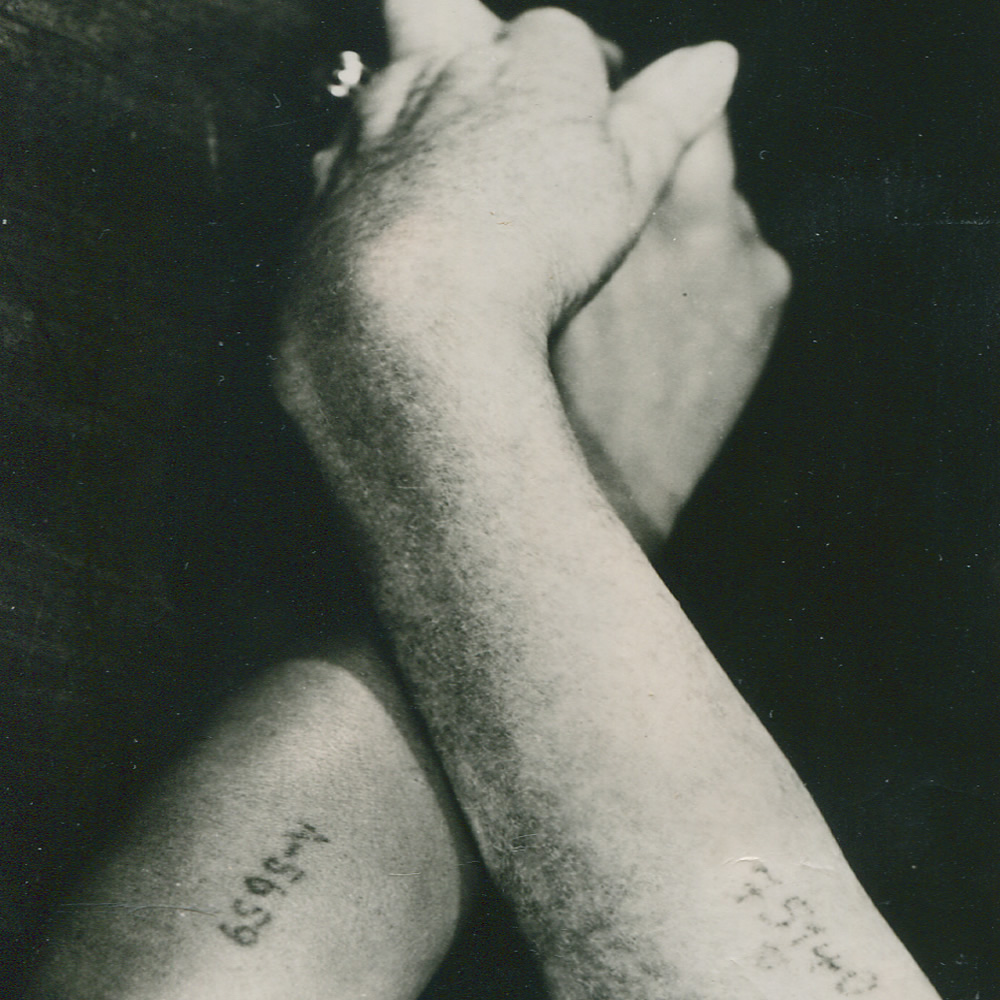

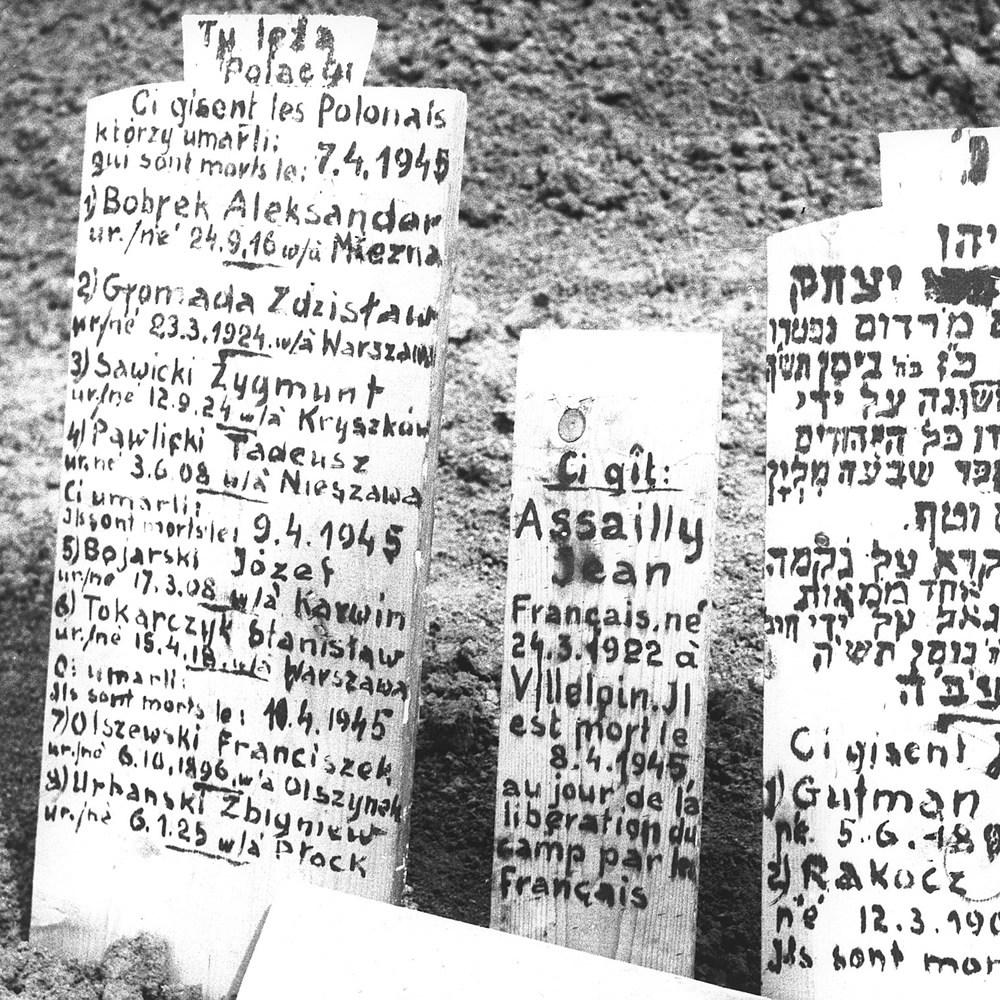

The liberation of Europe, which began in 1944, was a slow, messy process, but the emergence from genocide was also long and chaotic. The earliest estimates put the number of murdered Jews at between 5.7 to over six million out of a population of nearly 10 million living before 1939 in areas that had fallen under Nazi rule or domination. For the four to five million survivors, the end of the war opened up a new chapter that prolonged the suffering they had already endured. They had to learn how to live again in an environment from which they had been excluded, overcome memories of humiliation and live with the after-effects of the Holocaust. Very few Jews— approximately 60,000, some of whom died within the first few weeks after their liberation — came out of the extermination, concentration, transit and internment camps alive. They were lost in the mass of 30 to 40 million civilians and POWs who needed to return home. Some, such as the Jews of France, were repatriated in fairly swift order, while others joined the throngs of “displaced persons” (DPs). Nearly all of the 200,000 to 250,000 Jewish DPs, most of them Polish, ended up in camps again, this time run by the Allies, waiting to emigrate. This was one of the most important phenomena in the history of the postwar and post-Holocaust period.

Video

WHERE TO GO?

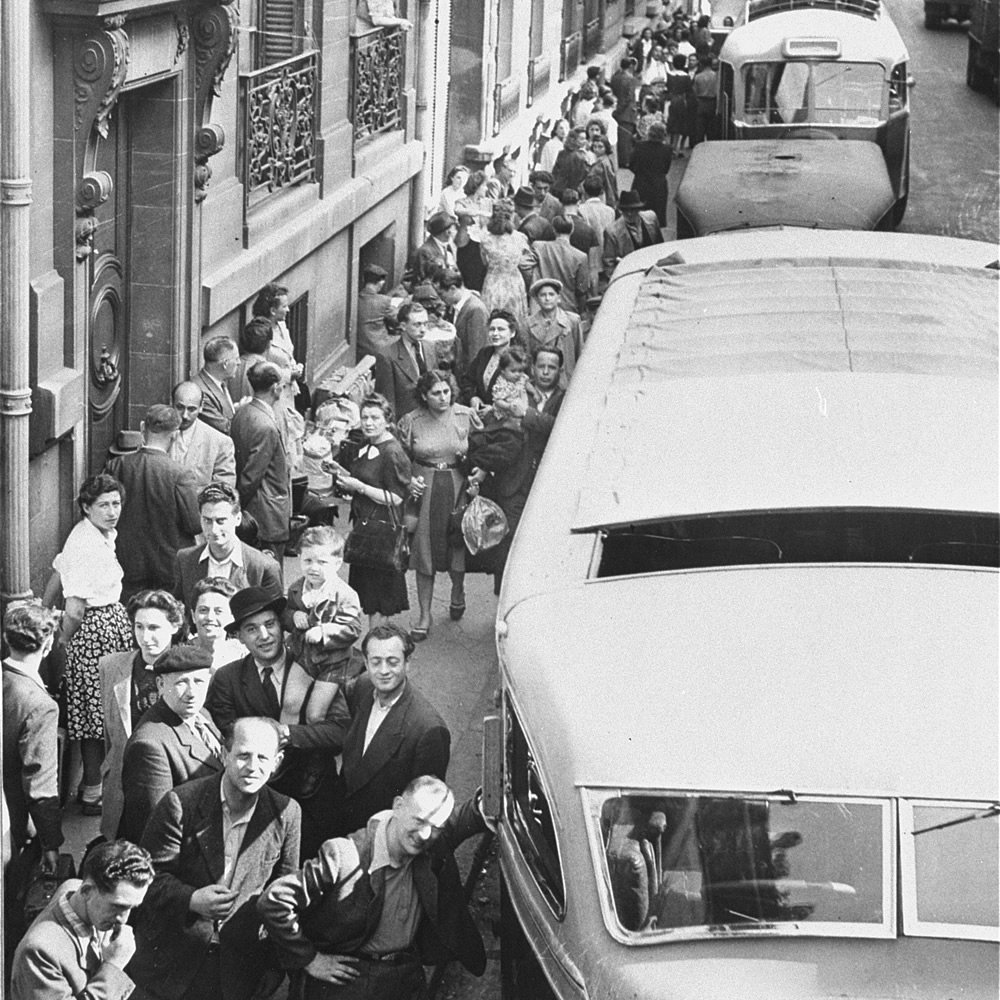

From April 1945 on, the French government repatriated 1,700,000 people in a few months, including barely 3,800 Jewish camp survivors. Like other countries, France set up administrative and healthcare facilities, such as at the Hôtel Lutetia in Paris, to welcome them. In Poland, on the other hand, where Jewish life had been almost completely wiped out, most of the refugees streaming back from the USSR could not or did not want to remain. Despite the murder of three million Polish Jews, they fell prey to post-genocidal anti-Semitic violence. “They shall never forgive us for what we have done,” said one Jewish historian at the time. Most of the survivors had no other choice but to leave again. These refugees crossed Europe, this time travelling West, often illegally, on an epic journey. Most transited through DP camps, in particular those that were eventually set up exclusively for Jewish survivors in Germany, Austria and Italy. Their ultimate goal was to leave Europe for good, including by transiting through other countries, such as France. Emigration became one of the main issues of the post-Holocaust period on an international scale. Most of the survivors went to the Americas, Australia and Palestine.

Video

ASSISTANCE AND MUTUAL AID

After the war, many Jews found themselves homeless, jobless and stateless, without resources or family. After years of physically and psychologically exhausting persecution, they needed outside assistance to help them start a new life. Governments and two international organisations, the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration and, later, the Intergovernmental Committee on Refugees, provided financial or material aid for reconstruction. But most of the help came from a myriad of Jewish organisations, a form of mutual aid that began during the war, which funded and organised massive social assistance for the reconstruction and preservation of European Jewish life. The American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee (Joint) contributed nearly $200 million, of which 7% went to France and 10% to Poland. American Jewish organisations gave displaced persons other kinds of assistance in addition to financial aid. Some met survivors’ basic needs, from housing to food and clothing. Others, betting on the future, focused on helping children (OSE) or on vocational training (ORT).

BACK TO LIFE

On 8 May 1945, the first “mixed” marriage in Berlin since the 1935 Nuremberg laws took place. In Paris, shops on rue des Rosiers and the workshops of Belleville gradually reopened. Despite the suffering they had endured, those who stayed tried to pick up the threads of “normal” life: family, work, studies, prayer, culture, politics and even leisure activities. They expressed their appetite for living, particularly in displaced persons camps, where nearly 250,000 Jewish survivors again found themselves in a closed-off world and an uncertain situation. But the desire to start a new life, rebuild communities and plan a better future somewhere else kept them going. As early as late summer 1945, most of the Jews in the Western occupation zones were grouped together in specially allocated camps, where they started new lives, got married, had children, printed makeshift prayer books, recreated schools and went back to work. In an ironic twist of history, the country where the plan to destroy the Jewish people had originated became one of the places where Jewish life rose from the ashes in the immediate postwar period.

OBTAINING JUSTICE

“A crime that remains unpunished.” That had been the prevailing view in recent decades until trials for crimes against humanity belatedly took place, especially in France. But some of those responsible for the extermination of Jews were tried, sentenced and executed as soon as the first Nazi-occupied areas were liberated. After the war, the Nuremberg trial addressed the issue of genocide. However, anti-Semitic persecution and massacres were perceived as being part of an overall policy targeting civilian populations in general. It took time and perspective to establish the difference in degree and nature. Obtaining justice also meant setting up mechanisms to return and make reparations for spoliated property, on which the survivors’ material survival often depended. Lastly, it also involved identifying certain Jews (ghetto policemen, kapos, Jewish councils, etc.) who were complicit in the Holocaust, whether voluntarily or not. Although very few in number, they were a stain that had to be washed away within the community.

THE FIRST STEPS TOWARDS REMEMBRANCE

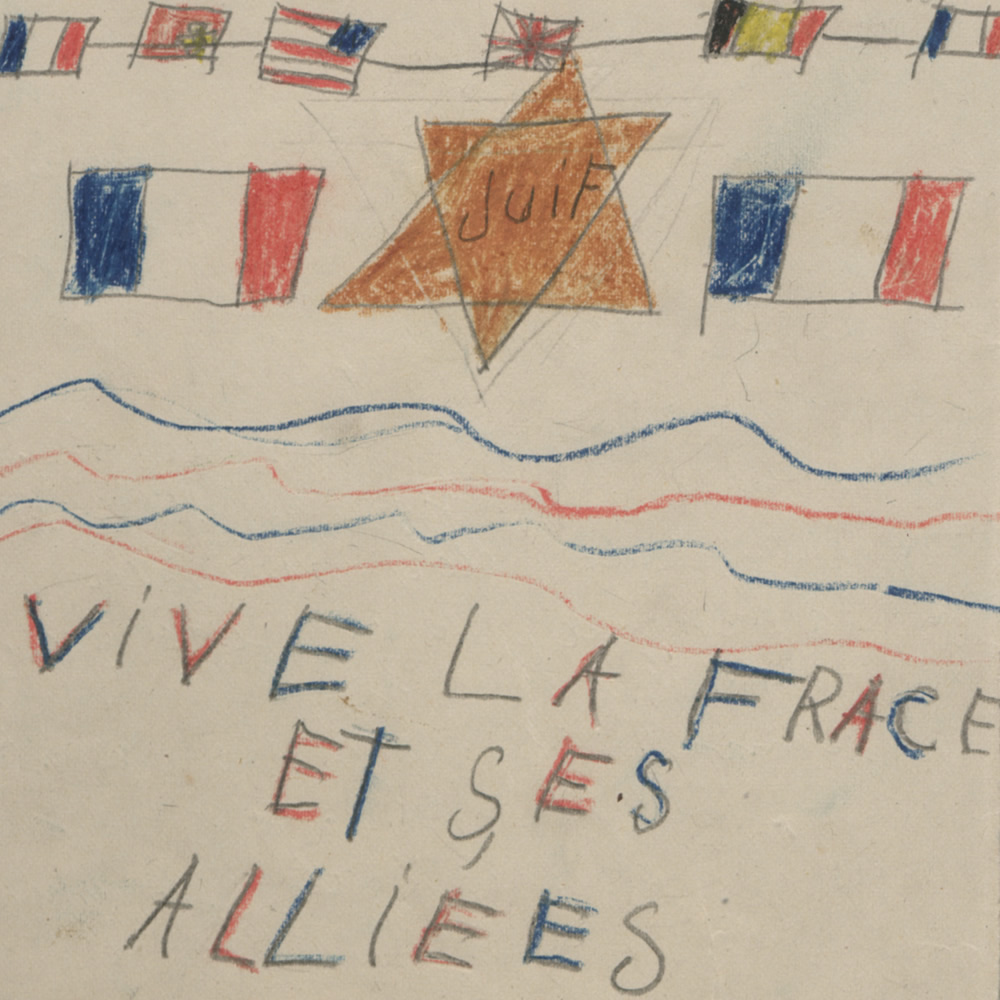

The idea that Holocaust survivors kept silent after the war out of modesty, shame and fear of not being heard in the context of rebuilding and reconciling European societies prevailed for a long time. It was partly true.However, nothing characterises the immediate postwar period better than the blossoming of Holocaust testimonies and first-hand accounts. Even before the war was over, in the midst of persecution, intellectuals, academics and rabbis organised the clandestine collection of traces of Jewish life threatened with extinction. Others, such as the members of the Centre de documentation juive contemporaine (Contemporary Jewish Documentation Centre) in Grenoble, amassed evidence of the persecution underway.

Even before the war was over, in the midst of persecution, intellectuals, academics and rabbis organised the clandestine collection of traces of Jewish life threatened with extinction. Others, such as the members of the Centre de documentation juive contemporaine (Contemporary Jewish Documentation Centre) in Grenoble, amassed evidence of the persecution underway. After the war, Jewish historical commissions were set up throughout Europe, at the same time as official research centres, with the aim of writing an early history of the catastrophe. These first steps towards remembrance, along with courtroom testimony, show how much about the extermination of Jews was known and documented, although the survivors only talked about their experiences amongst themselves and in relative isolation. As early as 1945-1946, funeral rites and commemorations took place and monuments and memorials were built.